Walter de Milemete utförde två stora illuminerade verk till den unge kungen Edward III 1326/27. Det ena är en kungaspegel, De Nobilitatibus, som vi tidigare studerat. Det andra är ett verk med namnet Secretum Secretorum. Det första verket har han sammanställt och skrivit, det andra verket är en avskrift på latin. Han har tydligen själv gjort kalligraferingen, men haft ett antal olika illuminatörer till sin hjälp.

Walter de Milemete made two grand illuminated works for the young king Edward III 1326/27. The first is a Mirror for the King, De Nobilitatibus, we have studied before. The second is a work, namned Secretum Secretorum. The first he has compiled and written, the second is a copy in latin. Obviously he made the calligraphy by himself, but have had several illuminators in his service.

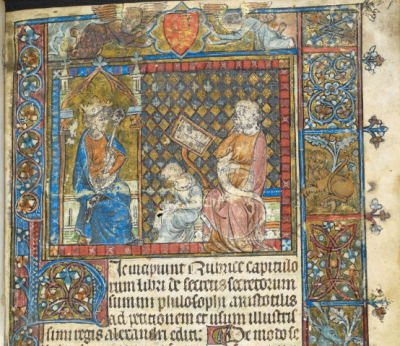

Secretum Secretorum inleds med en stor vinjett med en kung som lyssnar till en föreläsning av en man som bär den akademiska huvudbonaden och håller handen i talegest. Bilden är i ganska dåligt skick, för ett tag var tydligen verket utan skyddande pärmar. Där finns en pulpet med föreläsningsanteckningar och en skrivare gör anteckningar. Ovanför bilden håller två änglar Englands sköld. Man skulle därför kunna tro att kungen är Edward, men det är Alexander den Store. Och den som föreläser är filosofen Aristoteles. Texten under bilden förklarar det hela: Hic incipiunt Rubricae capitulorum libri de Secretis Secretorum summi philosophi Aristotilis ad peticionem et usum illustrissimi regis Alexandri editi.

Secretum Scretorum begins with a big vignette with a king listening to a lecture by a man in the academic cap, holding his hand in a speeching gesture. The picture is in a rather bad condition; for some time the opus had no protecting cover. There is a pulpit with lecture notes and a scriber makes notes. Over the illumination two angels are holding the shield of England. It is easy to think that the king is Edward, but he is Alexander the Greate. And he who lectures is the philosopher Aristotel. The text below explans: Hic incipiunt Rubricae capitulorum libri de Secretis Secretorum summi philosophi Aristotilis ad peticionem et usum illustrissimi regis Alexandri editi. BILD f.1r

BILD f.1r

Vi vet, att Aristoteles 348 BC blivit kallad av Filip II av Makedonien för att vara privatlärare åt sonen Alexander. Hela verket utger sig alltså för att vara Aristoteles undervisning av Alexander. I ett hundratal korta kapitel avhandlas en mängd olika ämnen i boken. Varje kapitel inleds med en stor vinjett med kungen (Alexander) i olika sammanhang, i de flesta av bilderna blir han undervisad av Aristoteles, i andra sitter han omgiven av sitt råd, som anakronistiskt består av både kyrkliga och världsliga rådsherrar.

We know, that Aristotel in 348 BC was summond by Philp II of Macedonia to be private teacher for the son Alexander. The whole opus is ment to be Aristotels teaching of Alexander. In about one hundred short chapters are a lot of subjects diskussed in the book. A big vignette with the king (Alexander) introduces each chapter. In most of the pictures he is lectured by Aristotel, in others he is sitting with his councel surrounding him. Anacronistc there are both bishops and secular noblemen.

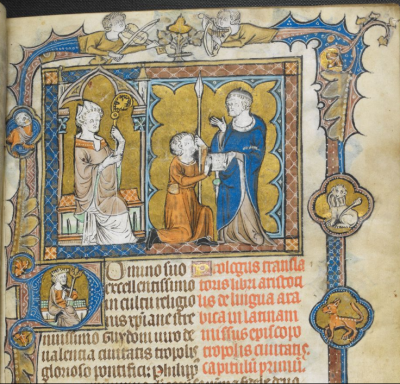

Boken berättar själv om vägen till den föreliggande texten: Den är översatt till latin från arabiskan av en Philip, med dedikation till en Guido de Valentia, biskop av Tripoli. Man menar att den här översättningen till latin tillkom i början av 1200-talet. Den arabiska texten skulle härstamma från 7-800-talet. En Johannes skulle då ha funnit texten på grekiska och översatt den först till kaldeiska och därefter till arabiska. På bilden tar Philip emot verket av Aristoteles. Biskop Guido övervakar händelsen.

The book tells us by itself of the way to the presnet text. It is translated to latin from arabic by a Philip, with dedication to a Guide de Valentis, bishop of Tripoli. It is ment that this translation was done in the beginning of the 13th centuary. The arabic text is said to be from the 8-9th centuary. A Johannes had then found the greek text, translated it to chaldeian and then to arabic. On the picture Philip receives the opus from Aristotel. Bishop Guido is supervising the event. BILD f.6r

BILD f.6r

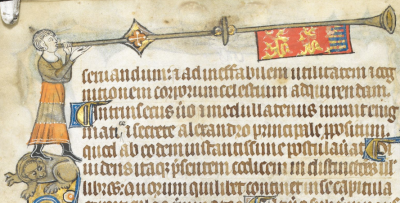

De prick-randiga tyger som vi är intresserade av, de förekommer mycket sparsamt i det här verket. En del påminner om bilderna i De Nobilitatibus. Kanske kan likheterna bero på att någon av illuminatörerna arbetat med bägge verken. De tre marginalfigrurer som jag hittat, som har dräkter med prickrandiga tyger, är musikanter.

The dotted striped cloth we are interrested in, they appear very rare in this opus. Som reminds of the illuminations in De Nobilitatibus. The likeness can depend on that some of the illuminators have worked with both the opus. The margin figures, wearing dresses of dot striped cloth, I have found, are musicians. BILD f.7v

BILD f.7v BILD f.9v och f.11v

BILD f.9v och f.11v

Det finnns ännu en bild med prickrandiga dräkter, det är en vinjett, där tre riddare i surcot med prickränder står framför Alexander, som håller handen i en talegest. Så gör också Aristoteles på en bänk i bakgrunden i marginalen. Tydligen ger Alexander order eller anvisningar till riddarna, understödd av Aristoteles.

There is still more a picture with dot striped dresses, it is a vignette where three knights with dot striped surcots are standing before Alexander. He hold his hand in a speaking gesture, as do Aristotel in the background in the margin. Obviously Alexander gives orders or instructions to the knights, supported by Aristotel. BILD f14v

BILD f14v

Nederst på samma sida står en riddare, iförd en surcot med prick-linje-rand, mellan två sköldar: – kungens av England och tronföljarens.

At the bottom of the same side there is a knight in a surcot with dotted line. He is standing between two shields, beloning to the King of England and the Heir. BILD f14v nedre marginalen

BILD f14v nedre marginalen

Det finns ytterliga några bilder, där mantlarna har en kantning av prickränder. Det är vinjetter som inleder nya kapitel. Man ser Alexander omgiven av sitt råd. Aristoteles på den tredje bilden har inte sådan kantning på sin dräkt.

There are somee more pictures, where the mantels have an edge with dottet line. They are all in vignettes, introducing new chapters. Alexander is seen, arounded by his court. Aristotel on the third picture has not such an egde on his garment. BILD f.33v

BILD f.33v BILD f.34v

BILD f.34v BILD f.35r.

BILD f.35r.

Aristoteles finns i en marginalbild med knäböjande elev (?). Här har bägge mantlar med kantning av prick-ränder.

Aristotel is found in a margin picture with a kneeling pupil (?) before him. Here both of the persons have overcloth with dot striped edges. BILD f.39v.

BILD f.39v.

Det här är de dräkter med prickrandiga tyger jag kunnat hitta i Secretum Secretorum. Huvudpersonerna har inte dräkter med prickränder på det sättet som bifigurerna har. Personer med högre rang kan ha en prickad kant på mantlarna, men de tvärrandigt dekorerade dräkterna finns på musikanter och några riddare. Är det uttryck för en social skillnad?

These are all the dresses with dot striped cloth I have found in Secretum Secretorum. The main figures do not have dresses with dots and lines as the secondary figueres have. Persons with a higher rank can wear at dotted edge on their mantels, but the cross-banded dresses will be found on the musicians and on some knights. Is this en expression for social differences?

Nu har vi gått igenom dräkterna. Men det finns två bilder som jag inte kan låta bli att ta med, för de är intressanta, kanske mest för riddare och fighters. Den första är en kanon av samma slag som i De Nobilitatibus, en pot de fer. Den kanon som finns i det verket sägs vara den första kända avbildningen. Då måste detta vara den näst äldsta.

Now we have noted the dresses. But there are two more pictures I will allow me to include. Because they are so interresting, most perhaps for for knights and fighters. The first is a cannon of the same shape as in De Nobilitatibus, a pot de fer. The cannon in that opus is said to be the first known representation. Thus this one must be the second oldest. BILD f.44v

BILD f.44v

Om vi fick se en unik bild i De Nobilitatibus av Walter de Milemetis, som också finns här, så är han dock inte sämre i Secretum Secretorum, då han bjuder på ännu en unik bild. Den bild jag tar med till sist föreställer inte en spis med skorsten. Männen använder inte blåsbälgar för att underhålla en eld. Det här är nämligen en Cornu Alexander Magni, ett kollossalt horn eller trumpet, ett stridsinstrument, troligtvis är det här den äldsta bilden av en cornu. I texten på sidan står det: Et est instrumentum terribile quod dicitur multis modis. Ljudet av detta fruktansvärda instrument kunde höras upp till 60 miles (dvs nära 100 km).

If we were lucky to see an unice picture in De Nobilitatibus of Walter de Milemete, here duplicated, so will he give us another unice picture in Secretum Secretorum. The picture I choose for the final is not an oven with a chimney. The several men are not using their bellows to maintain a fire. This must in fact be a Cornu Alexander Magni, a enormous horn or trumpet, an instrument for war. Probably is this the first representation of a cornu. In the text on this page is read: Et est instrumentum terribile quod dicitur multis modis. The sound of this terrible instrument could be heard up to 60 miles (aprox 100 km). BILD f.42v

BILD f.42v

För att förstå Secretum Secretorum bättre, framför allt med latinet, har jag haft nytta av: James, Montague Rhodes: The Treatise of Walter de Milemete, Oxford 1913.

To better understand Secretum Secretorum, especially with the latin, I have had a good use of: James, Montague Rhodes: The Treatise of Walter de Milemete, Oxford 1913.